A Founder’s Guide to Calculating CAC and LTV the Right Way

A version of this article was originally published on TechCrunch.

As a former venture capitalist, I always tell founders that the most powerful tool they can employ while fundraising is a data-driven pitch.

Leading with data is even more valuable during periods of uncertainty and market volatility. With investors looking to de-risk their investment decisions, coming to the table with hard evidence portraying your company’s growth potential is the key to success for companies fundraising.

Volumes of valuable, real-time financial data are now at our fingertips because of cloud software, but without proper guidance — or data fluency — founders and investors alike are missing out on the opportunity to leverage these assets. I’m a firm believer that greater data fluency not only unlocks potential for individual companies, but also an entire generation of founders from traditionally underrepresented backgrounds.

Zooming in a bit further, there’s one metric that companies must get right in order to demonstrate their potential for growth and attract investors: their LTV/CAC ratio.

What is LTV/CAC and why does it matter?

Lifetime value (LTV) and customer acquisition cost (CAC) are two of the most common metrics used by investors and companies alike to provide a cost-benefit analysis and ultimately predict a company’s value.

When companies acquire customers, the right way to view that customer is not just as a one-time purchaser but as a long-term cash-flowing asset. LTV helps both investors and companies calculate the long-term potential value of its customers, especially when they are expected to continue paying for goods and services over a sustained period of time.

To acquire these customers, companies have to spend capital (using equity, debt or their free cash flow) on tactics like paid ad campaigns, sales personnel and more. The total expenses that contribute to acquiring a certain cohort of customers is considered the CAC for that cohort.

Investors use LTV/CAC to measure whether a company’s short-term investments into sales and marketing are creating or destroying value for the business and determine if additional capital will help the business scale efficiently. Measuring the ratio between LTV and CAC allows investors to predict if giving a company more money to spend on CAC will yield a positive or negative ROI.

A low LTV/CAC ratio is a red flag, as it shows the company is not efficiently acquiring high-value customers and will ultimately require more investment to grow. On the flip side, a strong LTV-CAC ratio indicates that injecting new capital can help accelerate growth exponentially.

Where do companies go wrong?

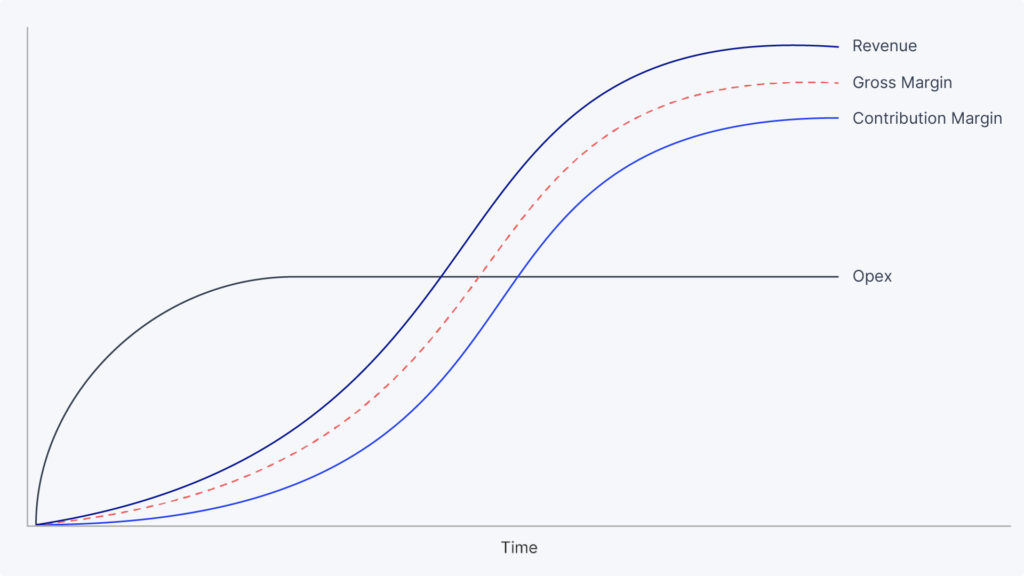

Many common mistakes boil down to one thing: using the wrong metrics to tell your story. Something I see often is founders calculating LTV/CAC on a revenue basis, when in reality, calculating LTV/CAC from a gross margin basis is imperative for growth financing.

For example, an e-commerce company that purchases an ad impression may subsequently generate revenue from the customers that sign up, but the cost of web hosting, shipping, inventory, etc. still needs to be factored in to understand the net revenue.

For companies with high margins, there may not be a major difference between revenue and gross profit, but for companies with thin margins, the fulfillment costs to service their customers can be the differentiator between a capital-efficient business and one that’s eroding value.

Leaning solely on revenue does not paint the most accurate picture for investors and can be a red flag.

Another common sticking point is actually much more tactical and involves going back to the basics of calculating LTV/CAC. While it’s easy to overlook, plugging in the right numbers — and accessing data from the right sources — is essential for accurately portraying a company’s growth, and, more importantly, using data to establish trust with investors.

So how do you actually calculate LTV/CAC?

The traditional factors that qualify as customer acquisition costs are any type of paid acquisition. This includes pay-per-clicks, referral channels, revenue sharing to referral partners and more. As such, the more a company spends on sales and marketing, the more likely they are to generate revenue through those channels.

This calculation tends to become more complicated for early founders when you include factors like the salaries and commissions of sales and marketing employees, and other market costs.

Building a strong brand is something that can be amortized as the ratio of revenue-to-brand spend rises over time. Since market costs like brand awareness rise with revenue, it’s important to include that in CAC to give the most accurate representation of the business’ growth.

If other factors are included in CAC, it may appear that operating costs are rising out of sync with the company. Ideally, as a business expands, the operating costs will become static, and there will be revenue to offset those costs, which is why it’s essential to use the correct numbers when calculating CAC.

Data from payment processors like Stripe or PayPal can be an excellent source for calculating LTV, but it’s important to evaluate this data amid groups of customers on a cohort basis. Simply looking at monthly gross margin on a profit and loss statement can be misleading, because different business models present different realities on the true lifetime value and ROI of a customer.

Take a furniture business as an example: When a customer purchases a bed, the company will benefit from that payback almost immediately. However, since most consumers only purchase a bed once about every eight to 10 years, there won’t be continuous payback on the CAC. Alternatively, a software subscription customer may pay back that CAC gradually over several months, but the customer’s ongoing subscription will have a higher return over time.

Sample LTV to CAC, January 2019 to December 2020

With this approach, there’s a tension that gives way to two fundamental perspectives on LTV/CAC. First, the macro view, which, as described above, includes factoring in all sales and marketing costs and makes up a more conservative approach. The micro view is to focus on costs per lead, and demonstrating how efficiently a company can scale individual transactions to fuel its growth.

While founders with an eye on high valuations may hesitate to follow a conservative approach, doing so can be pivotal for building trust with investors who will ultimately want to understand the company holistically. Because investors will want to see both the macro and micro views, the most successful companies will be able to use their data with these two approaches for calculating LTV/CAC.

In any fundraising pitch, investors are looking to answer one question: Can this company scale and grow efficiently in the long term? LTV/CAC gives investors a perspective on that — when the ratio is greater than one, the answer is yes. But on the flip side, a ratio that barely surpasses one is an indicator of a potentially bumpy road ahead.

Moreover, understanding how quickly a customer cohort will provide a ROI to the company, and how long they will continue to pay that back is critical for both investors and companies.

While these factors vary for every business, LTV/CAC data should be evaluated relative to an appropriate peer set, and never in isolation. For founders, seeing their company through the eyes of an investor can be a major step toward leveling the playing field.

While increasing transparency at the systemic level may seem daunting, data-driven storytelling is the greatest asset a founder has to increase their chances of securing capital. Yet, this can only be accomplished with a fundamental understanding of using company data to paint an accurate and compelling picture of your business’ potential.